“मेरी हद्द” (The premise of my existence)

“पंख” (Pinion)

“अवरोध की उड़ान” (Fenced Flight)

“अंतिम संस्कार” (Culture Death)

“कितनी गिरह?” (How many more Knots?)

“अल्ला कि गाँए” (God’s Cow)

“सपनों कि साज़िश” (Conspiracy of Dreams)

“अतीत का भविष्य” (Makings of past)

“काग़ज़ का फ़ूल” (Paper Flower)

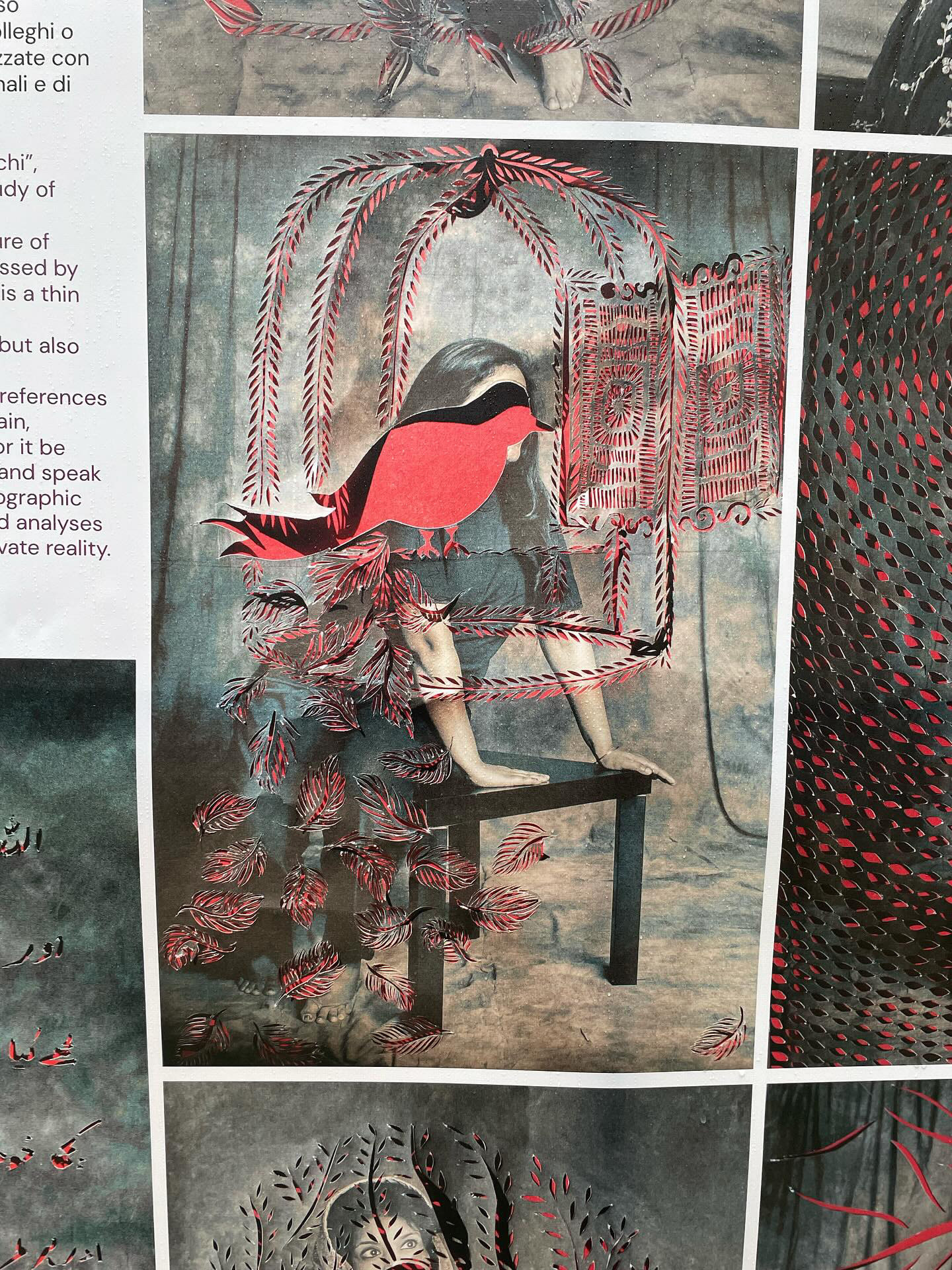

“क़ैद-ए-क़फ़स ” (Prisoner of Prison)

“एक अदभुत परिंदा” (Phoenix)

“मिट्टी के दायरे” (Circles in Sand)

“मुझसे मुलाकात” (Finding Me)

“सर पे छत” (A place to call home)

“मोम का पुतला” - (Statue)

”कटि पतंग” (Unconfined or Unhinged)

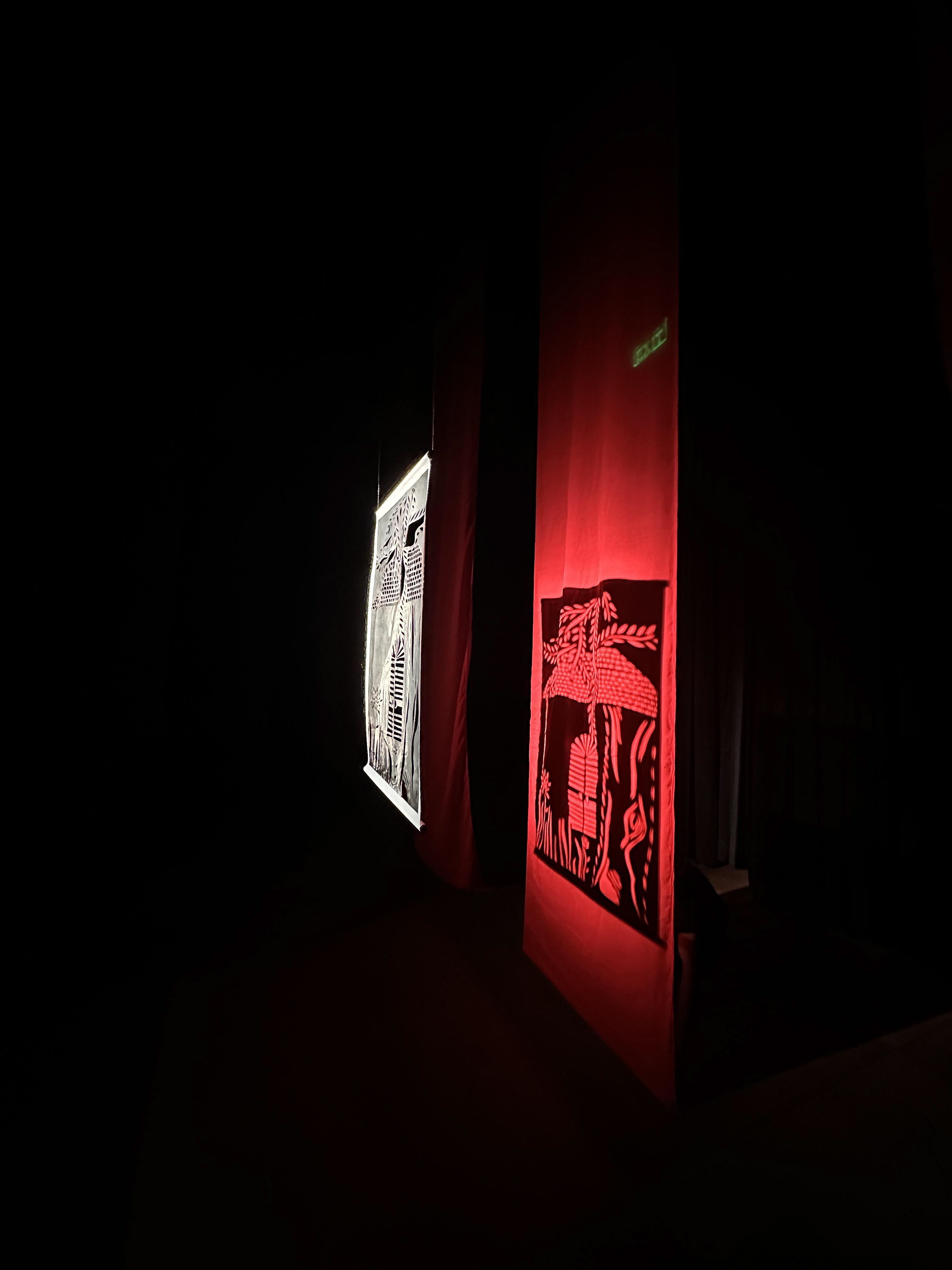

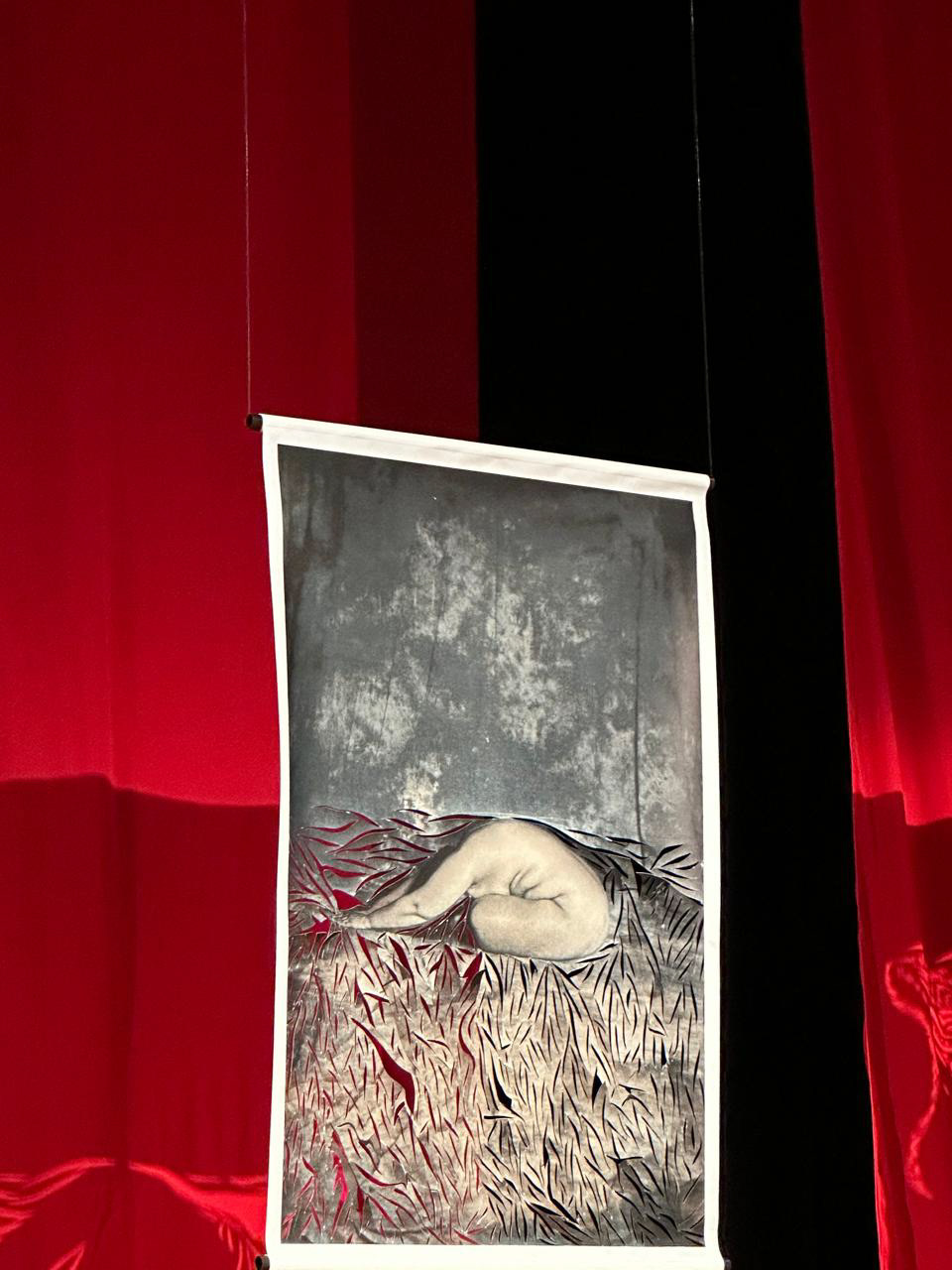

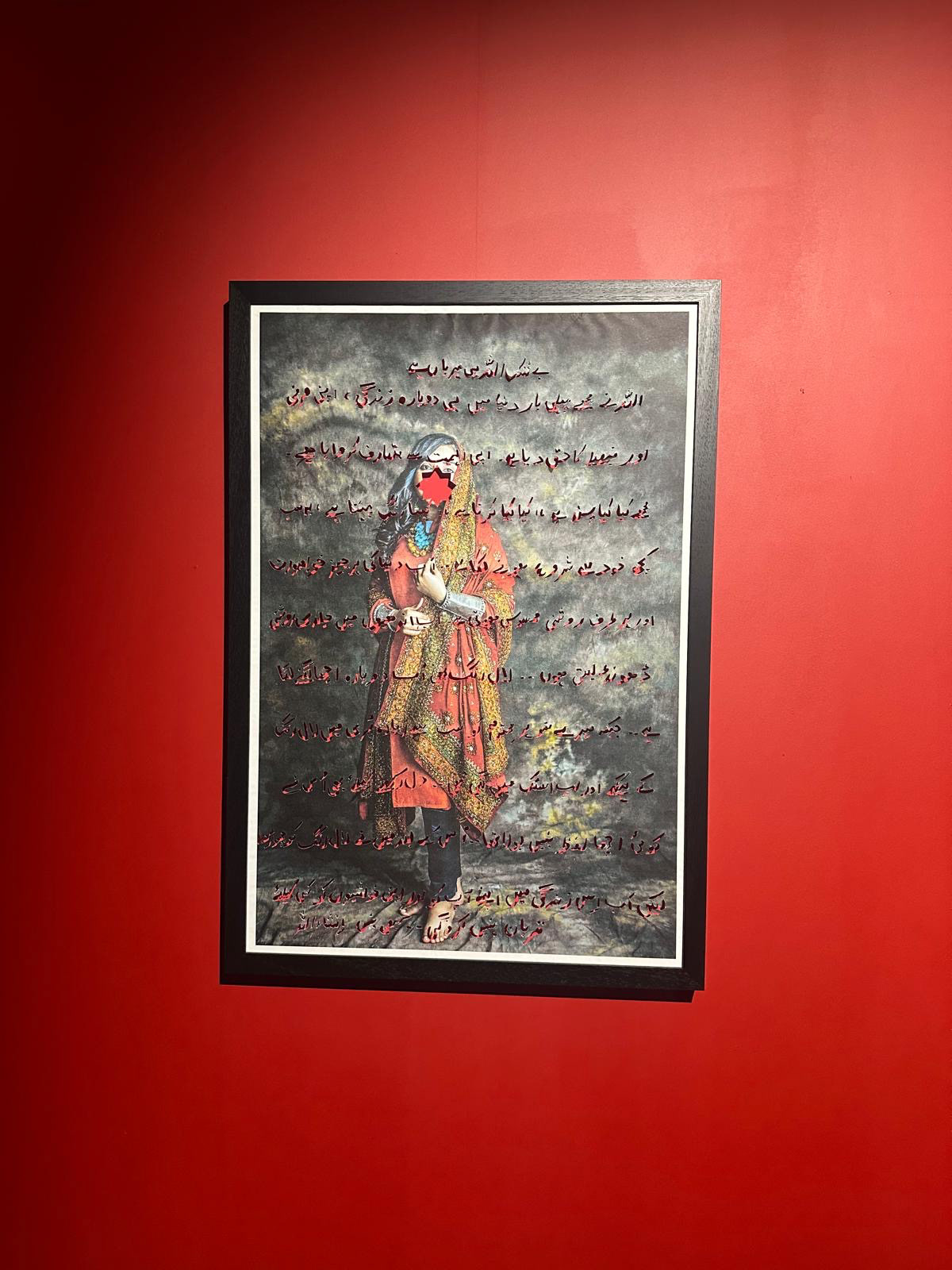

Derived from the ancient Asian form of torture -“Death by a thousand cuts” or “Lingchi”, “A thousand Cuts” is a series of portraits and stories that present a photographic study of patterns of domestic abuse in the South Asian community.

I have borrowed the metaphorical meaning of Lingchi to showcase the cyclical nature of domestic abuse.

The continuous act of chipping at the soul of the abused, is expressed by making cuts on the portrait of the participant.

The paper used to print the portrait is a thin A4 sheet, depicting the fragility of her existence.

I have kept the project at a domestic scale, using resources available within the home as a metaphorical reflection of violence occurring within the human space. The final artwork is photographed in a very closed, tight crop so as to express a sense of suffocation and absence of room for movement.

The red colour underneath the portraits signifies not just martyrdom and strength but also the onset of a new beginning.

“A thousand Cuts” is an effort to understand abuse from many different frames of references.

My intent was to create a metaphorical “waiting room,” where strangers meet and talk to each other without any fear of judgement or hierarchies. An imaginary space where conversations around abusive lived experiences

continue to happen. Where it is easy to come out. A room where you are heard, seen, understood and where you feel safe to leave your story behind.

We started by creating that room as a real space. A space in a church in Hounslow, UK. Many of us met there, several times over. We held hands and spoke at length. No one interjected the other. No one left the room midway. These initial dialogues led to the creation of a vector of faith between myself and the participants in this project. We then moved on to private one-on-one conversations and me photographing each survivor individually with their consent and their complete control on the way they want to be “seen.” Once I printed the images, the survivor then selected the image she wanted me to start making the cuts on and made suggestions on the metaphorical representation of their narratives through those cuts. From there on, it has been over a year and the conversations continue. Sometimes I listen. Sometimes I get heard… but we promise to “see” each other.

Through these conversations, we have collectively tried to study the journey of abuse from the private, intimate space where violence occurs; to its place in the public domain, whether it be in terms of how the private reality is subverted; decorated in public or that initial disclosure process when the survivor breaks their silence and speaks out to family, friends, neighbours, colleagues or even absolute strangers. This photographic study drawson interviews with 21 South Asian women (it is an ongoing project) and analyses the interactional and emotional processes of the first public disclosure of their private reality.

The long term intention is to bring narratives of abuse into the public discourse, arts and human spaces. In that sense, “A thousand Cuts” is an invitation for an open dialogue that allows both the survivor and the society at large, to explore concepts such as trauma, suffering, genetic and cultural predispositions, gender and identity politics without sacrificing their own vulnerability or risking confrontation.

In my discussion with one of the participants, who is of Indian origin, we had a very disturbing however, real conversation about how her perpetrators existed within “home”.

“Home” being a metaphorical term here describing not a physical space but energies… many energies and realms of individual and systemic consciousnesses, placed in relative positions to each other.

We spoke of how generations of human and societal conditioning formulated her understanding of simple feelings such as love, care and belonging. How she equated all of these feelings to some or the other form of coercive control and how that understanding itself helped perpetuate and in a sense normalise the verbal and psychological abuse that was meted out to her by her elders and society at large.

It is a very complex reality. Of being a woman. Also, of being a south asian woman. I started to find in me this urgent need to engage with this complex, yet very subtle reality.

So I reached out to Sayeeda Ashraf at the charity - Shewise UK. Sayeeda and I had been work colleagues in the past and I knew about the immensely important work she was doing in the field of helping survivors of Domestic Violence in becoming financially independent.

I discussed with her about my intent. Sayeeda along with Salma Ullah and Saima Khan from Shewise, have been extremely instrumental in helping me reach out to the survivors and initiate a dialogue that is ongoing ofcourse but is most importantly sheltered with appropriate safeguards.

The survivors who have very generously agreed to participate in this project, are each experiencing differing stages of trauma so it was important for me to ensure that our engagement doesn’t leave their wounds bleeding.

Captions for individual photographs:

Image 1 Caption: “कितनी गिरह?” (How many more Knots?): I married 2 people in my life. They were very similar to each other. I got divorced from both of them for the same reason. I married my 1st ex because he was a relative of my father and I married the 2nd ex because of honour. I lived with the 1st for 14 years and 8 months. And I lived with the second ex for 1 year but it is like 14 years.

My first exes uncle harassed me. Look how same this life story is. Two husbands. Same kind of husbands. My second husband agreed with my cousin, who is my sister’s husband… to harass me. My cousin started to threat me. He said “ your ex husband sent me your naked pictures. Come sleep with me." I cant go into details or I will go into a panic attack.

My cousin contacted my brother and my brother and my father came to kill me. He said “You talk to another person who is not your husband or brother or father.”

I have a lot of bad experiences in my life. I tried killing myself three times, because they pushed me to kill myself. My brother locked me in a room for three months and they would just come, give me food and go. I lost my memory in those three months. My mother took me out one day but my brother told me to go find food in the garbage because I dishonoured their family.

All of the family was against me. We were 7 daughters and 4 sons. Anyone who came in through the door, my father would give our hand to them in marriage.

Image 2 Caption: “मुझसे मुलाकात” (Finding Me): Once during our fights related to him keeping control on all my money, he started speaking badly about my mother and my upbringing so I started recording everything he was saying on my phone. I decided I will send the recording to my family. I went with my phone to my room. He came to the room, snatched my phone and held my neck tightly and said “women like you are worth killing. Let me see who will save you today.”

I pushed him and ran towards the door.

He ran after me and said “no one will protect you.”

I was so lost in that moment. I couldn’t even fathom where the elevator was.

I was crying so loudly. Like one cries when someone has died.

Just beneath our apartment there was a cash and carry shop. I barged into it. I begged the owner of the shop to help me call my family back in my country. He hid me in the store and said he will come after attending the customers.

I wasn’t able to breathe.

That man helped me call my mother. My mother asked me to call the police.

That shop owner helped me call the police.

Police came. They saw the marks around my neck and arrested him.

Meanwhile back home his family went over to my parents’ home.

When my father got to know of what I had done… he harassed my mother and hit her.

My mother said to me “what is happening to me… let it happen. Don’t take it on your soul. You protect your life. I wasn’t able to help you earlier but I cannot let you die like this. Don’t return to that man for my sake.”

Image 3 Caption: “मिट्टी के दायरे” (Circles in Sand): I remember as a kid, we were left outside to play. There was a lot of construction ongoing in our neighbourhood. Everywhere I looked, I saw a mountain of sand and cement.

I would pick a pebble from the street and make circles in sand. Was it because I was seeking the shelter of her womb everywhere? Did her womb protect me? Or was it the perception of protection that became my understanding for the rest of my life?

My mother’s womb. It’s from there that I started witnessing the violence. I remember the sound the cemented floor made when she was dragged by her hair through it. I was three. I have grown up learning that to be the only sound of music…

Image 4 Caption: “एक अदभुत परिंदा” (Phoenix): One of the recurring dreams I have had is that I am in a zone of war with two children and I am hiding to protect myself and my children. So I was always foreseeing danger. I would see my house becoming my jail and on the other side of it I could see panthers walking around. My husband was my first cousin. My mother-in-law came from a very abusive marriage herself and she chose to get divorce and work and become financially independent and support her children. The first seven years of our marriage was good. We were actually in love. But she didn’t like that. She perhaps had an issue with couples being happy. It could be any couple, including her children. So in that sense if I look back at my story, I see her as the perpetrator, but the irony is that at one point she was a victim herself. There were days when I would stuff a cloth in my mouth while crying so my children couldn’t hear me because it was so painful. He would threaten me that if I left him he would make life hell for my entire family. Even if I would go back home at times to my parents, he would call incessantly or show up drunk at the door. So I remember once after a similar incident, I went back home with the kids and saw all the windows were smashed and there were shards of glass everywhere. I remember the trauma my children went through. With all the challenges we’ve had… it’s almost like you get buried and then you rise again. It’s like the phoenix, you rise like the phoenix.

Image 5 caption: “सर पे छत” (A place to call home): I wouldn't say we were a typical Asian family. My dad kind of isolated us. We weren't even allowed to speak our language. It was only English all the time. And my dad, he worked in like all good jobs like first he worked at the embassy then he worked at the bank. I remember how violent my mum and my parents relationship was my dad would get angry at my mum sometimes and he'd hurt her. I think I was very, very little. I remember him, like, silently banging her head on a wall and the blood staying. But on the outside, when you look at our family, we were well dressed, we had nice things, my dad spoke well, we were all like educated well, so on the outside, we all looked really good and our family looked really nice. When I was 16 my mother refused to support me any further. I didn't really have a place of my own And I was either living with friends or boyfriends. My mom treated my brother very differently to the way she treated me and my sister. Our needs as a girl is not important. If I want to study, that's not important. I mean, if my brother wants to study, yeah, that's important. And so I think that's why when I'm in these abusive relationships with these men, it's their needs first. I always remember my mum working. She'd go food shopping, I'd go and help her. My brother wouldn't help, my dad wouldn't help. So that's the kind of life I was brought up in.

Image 6 caption: “काग़ज़ का फ़ूल” (Paper Flower): He was divorced and 11 years older than me. I tried to resist. I had just graduated. But because my family was going through a bad time at that time. My father was critically ill. We were struggling financially and you know that social pressure. So my mum said “look this is a very good option and you won’t get this again. You are getting to go to London.” As a girl in south asian background, you are always raised to be submissive. You cannot have your own say. “A good girl always says yes.” Then he went back to London and I joined him in 2013. Thing didn’t seem right. He wanted children. He gave me an app to check my ovulation days. After or before that I was nothing to him. He tried so much to get me pregnant. It was like a job for me and it was a horrific job. Then I had my daughter. Not to mention the abuse from my in-laws it was horrific they used to control every single move of my life. I used to cry all the time and my husband was enabling all of it. But now I know, it was not their behaviour but the lack of love and empathy from my husband that made me so unhappy but back then I always thought he loved me a lot because that’s what he would say to me. I decided to live with him for the sake of my kids meanwhile I worked on myself. I learnt driving. I applied for a job. He dissuaded me all the time. He psychologically abused me. He used to tap my phone, my calls. We had cameras everywhere in the house. I felt like I was in a prison.

Image 7 Caption: “मेरी हद्द” (The premise of my existence): My parents brought me up with a lot of love. I finished my studies and they I became a school teacher. Someone brought a wedding proposal and the family liked me. The boy came. When I saw him I started to cry because he was much older than me. He was 22 years older. But my family told me “Its ok. You will have a lavish life. If he is older then he will obviously love and respect you.”

We got married and I came here to UK. For a year he kept me well and then I gave birth to twins. So once the kids were born my mother in law started to taunt me and a lot of fights started to happen. It was like, they wanted children and that I gave birth to so my job was done.

I remember the words “The machine to produce children has arrive now make as many as you can.”

They kept my and the kids passports with them. I was scared. They would not allow me to feed my milk to my own children. They would snatch the kids from my arms.

In a few years he filed for divorce. He tried to get full custody of the children because his family knew that if the kids came to me even for a few days then he would have to pay me some allowance.

He threatened my kids that if they say that they want to stay with their mother then their father would make sure to never let them see me.

So the children said in court that they want to stay with their father. He finally got the custody of the children.

Since then, I get to see my children twice a week for a few hours each.

Image 8 Caption: “अल्ला कि गाँए” (God’s Cow): It was my father and his elder brother’s family that lived together back home in my country. This is the time of my childhood. My cousin, who was the son of my uncle. I was about 5 to 6 years old. He started sexually abusing me. As a child I did not know what was going on but he would always ask me not to tell anyone. He was about 18-19 years old at that time. Our family then moved to London. And in our community it was felt that children who grow up in London and go out to malls etc, get spoilt so they should be married off to a man from our home country. So my mother’s younger sister convinced my father to get me married off to a man who was around 16 years older than me. I was 15 and still in secondary school. After the marriage, I came to London and he stayed back to do his paper work and he was meant to follow me to the UK once his visa came through. However during that time our family found out that the father of my groom was sexually abusing his own daughters. So my family got me divorced. However, this brought shame to my family. There was this typical scenario where concerns came up about what will society say about having a divorced daughter sitting at home. What will our relatives say! So when my cousin, who had abused me in my childhood came forward to ask for my hand in marriage… I wasn’t ambitious. I was not career oriented. I was a simple, quiet girl who always did what her family asked of her. I was “Allah’s cow.”

Image 9 Caption: “क़ैद-ए-क़फ़स ” (Prisoner of Prison): My husband from the very beginning told me that I will not keep you with me. I got married to you only because my parents insisted. From the onset itself he kept forcing me to return to India. I kept hoping he will fix his behaviour but he didn’t. One day he finally threw me out of the house. For the 8-9 months I lived with my husband, he mentally tortured me to such an unimaginable extant. He would not give me a penny. I wasn’t register at the surgery. I wasn’t even given food. He would come home bring his non veg food eat it and he wouldn’t bring anything vegetarian for me. So I would go hungry for days. He never let me get out of the house.. Once I fell seriously ill but he ignored me and did not take me to the doctor. He would torture me so much. I begged him to keep me with him. I begged him to not throw me out of the house. A middle person got us married. I saw him for the first time on the day of our marriage. I was 33 when I got married. One year after my brother got married and brought a wife home. For several years my parents looked for the right man for me but they never found someone who was good enough. People known to us would ask my father why I had been sitting at home for so many years but my gather would always say that he would not get his daughter married until he found the right man. Maybe it was in my destiny to marry this man which is why my father chose him for me. I was obedient. Wherever my father told me to marry, I got married.

Image 10 Caption: “पंख” (Pinion): I was 21. Everyone was pressurising me to marry and I kept rejecting offers and it bothered everyone. So I just said yes. I was too much into my studies so I couldn’t be bothered.

Within a month or two of our marriage he started forcing me to have a kid, It became too much. So I asked him if I could study further because that was my plan. Suddenly it looked like everyone in his family froze. They started complaining about the fee and how they couldn’t afford to pay it. So I decided to do a job but they refused to that as well. “Not possible they said. What will people say that we got an educated daughter in law because we want to make her work?” I started learning to drive. But my husband discouraged and ridiculed me by saying “at least clear the theory. I dont think you are capable of that as well.” I am not going to lie, he had completely shattered my confidence. I felt like I was capable of doing nothing. I was not allowed to make any friends. If someone came home also and I tried talking to someone, I would be told later not to contact anyone. I was not allowed to go out anywhere. I once wore clothes of my choice so I was immediately asked to change on the pretext that “what will people say! To the. Kind of clothes you are wearing.” It were such little and petty things… the minutiae of everyday life … the control. That I used to say to myself “I am overthinking.” Also, when you have not grown up witnessing such coercion then you dont even recognise the red flags.

Image 11 Caption: “अवरोध की उड़ान” (Fenced Flight): Let me tell you that I was a star before marriage. I earned a degree in finance and in my family no woman had this degree ever and I had a job. I was the youngest daughter so I was the envy of my brothers and other siblings.

When I got married, within 15 days I realised this marriage was really wrong for me. But when I was getting married, my sister told me “if anything wrong happens to you… please don’t tell anyone. Because I am fixing your marriage. So just let me know, dont tell anyone else.” So I kept quiet and I thought maybe marriages are like that because I have seen men back home are quite strict. So I kept quiet.

He started threatening me that if I say anything to anyone I will be deported from the country. And back home I have an aging father… he asked me to think about all of that.

He used to give me some money but he would keep counting.

Then I gave birth to my daughter. It was a difficult delivery. No one came to the hospital and when I got home my husband mistreated me. Around 2014, he stopped me from using the phone. I wanted to take pills so I could not get pregnant again but he stopped me. He would physically and verbally abuse me. He would lock me in the room and slap me and hit me with a towel.

He would treat me like… back home you know “a goat. Who always gave birth to 8-9 children and eat food and that’s it.”

My children suffered a lot of emotional abuse too. Ive been through all forms of abuse - emotional, verbal, physical, sexual. You name it.

Image 12 Caption: “अतीत का भविष्य” (Makings of past): I was young when I had some growth on my chest. People started talking. Some said I had drunk some potion. People turned our life into hell. A marriage offer came from a man in UK who was undergoing treatment for schizophrenia. My mother said “this is your way out.”

I took it. I was 16. When I reached London I was taken to the hospital to meet him. When he was not on medication. He was violent. When he was on medication. His family was violent.

Amidst my abuse, my children were born.

One day I escaped with my children and I went and sat in the middle of the road knowingly that I could be killed here but I said no, I’m not going back to that house because that family will kill me anyway. Traffic was stopped. Police came but did not help. I was sent back. My children grew up watching the abuse. My son is 50 years old now. He’s decided to not have children. He doesn’t want to carry his father’s blood line forward.

But you know while I was going through all of this abuse, I started to volunteer for women’s organisations… to empower other women.I had nobody there for me but they have me. So I tell them:

Learn English. Get your driving license. Become independent. Don’t rely on anybody. I encourage them. No one encouraged me. I had to do it myself but now I am there for other women.

Image 13 Caption: “सपनों कि साज़िश” (Conspiracy of Dreams): I have a very good childhood. And my father was very hardworking. He earns for us and he gave us the gift no one can give me like that education. I am a masters from Pakistan. And I was very sheltered. I was not like, I have to go out and work. So it was all my in head that one day I will be like married and I'll find my prince and all that.

Yeah, boy was treated as an investment? That they will look after them in their old ages because daughter has to leave one day. So that was all in my thinking and it was all in my mother head because she don't know anything about other than this box and I was also don't know.

So the marriage to this man happened after I see him once in the presence of everyone. He was Danish national living in England.

But after reaching here he start changing he like keep distancing from me. His mother was verbally abusive. He was also verbally abusive. I couldn't understand because I'm very new to England. And I thought maybe people are like this. But the planning behind the marriage was to run his brother food business. So it just came to me one night when I just refused to work without payment. So he beat me harshly. And he said, he just brought me here to run his brother's business. So it was a fraud marriage.

It took me five months to leave this marriage. because that day my ex -husband went to deliver rice or something to his brother's shop and he forgot in rush to close the door and I found that the door opened and I ran away.

Image 14 Caption: “अंतिम संस्कार” (Culture Death): I didn’t believe until now that it is my story too even though I started to witness the violence from inside her womb.

The only vivid childhood memories that I have are of watching her being dragged by her hair around the house in front of my cousins. I remember hiding behind the door and witnessing all of it. Or was I standing in the room? I am not so sure. Where were my brothers at that time? I cannot recollect. I think I was three-years-old. That year somehow stays with me. That was also the year I remember sleeping in my parents bed alone. It was afternoon. I wasn’t in my nappies… no. I think by that time I had just grown out of my nappies. My cousin. I remember him on me… no one else was there in the room.

She wasn’t allowed to do anything except for bringing us up the way he wanted us to be brought up. She would cook and clean. He had two sisters, each of whose one son lived with us. They would boss her around as well and enjoy watching her being beaten up.

Many nights he would return at early hours of the morning drunk. I remember his head inside the toilet seat. His body hanging like a wet cloth, loosely attached to the scruff of his neck.

I am 41 now, I still carry the trauma of my childhood like an invisible limb. My mother has died. Her perpetrators remain alive. Not just the man. Neither all those men or women. Abuse exists within our culture, our genetic predisposition.. the gendered narratives that are fed to us.

Image 15 Caption: “मोम का पुतला” - (Statue): “I am not able to understand anything. Nothing. I am not even getting any dreams. I don’t feel like doing anything. I don’t feel like doing anything. I am not feeling like doing anything. I am not feeling angry with anyone. I am not able to understand what is happening. I am not able to understand what to do and what not to do. I am neither feeling sad nor happy, I just keep living like this. I am not able to understand anything right now. I am not able to understand anything. I am saying the same thing, I am not able to think of anything. The doctor has given me medicine. I am not able to feel like doing anything. I am not able to understand anything. I am saying this again and again.”

Image 16 Caption: ”कटि पतंग” (Unconfined or Unhinged): In my head I created a calendar, in which every second day… a mishap happened. Life kept going on.

But the biggest damage was how possessive he was. What I wore. What I did. Whom I spoke with. Where did I go. He dictated everything. He told me what colour to wear and what not to wear.

If I even went to my parents’ home he would call a 100 times.

Everything I did was monitored.

If I wore good clothes… he would just tear the clothes.

I used to love wearing black colour but because of him black colour permanently got adorned in my life because he wouldn’t let me wear another colour.

He would speak lowly of me in front of other people to stifle my confidence.

I bore two daughters from this marriage. The abuse continued and this started impacting my children.

My youngest daughter became very quiet. Slowly she started losing her hair and she ended up with alopecia.

Ofcourse amidst all of this abuse life goes on. We eat food. We go on family holidays. We meet people… life has a way of staying normal amidst all its abnormality.

BFF MANTOVA

CITY HALL UK

UK BILLBOARD CAMPAIGN

BFF MANTOVA

CREATIVE WOMENS HUB UK

BFF MANTOVA

CREATIVE WOMENS HUB UK

BFF MANTOVA

CREATIVE WOMENS HUB UK

BFF MANTOVA

BFF MANTOVA

BFF MANTOVA

BFF MANTOVA

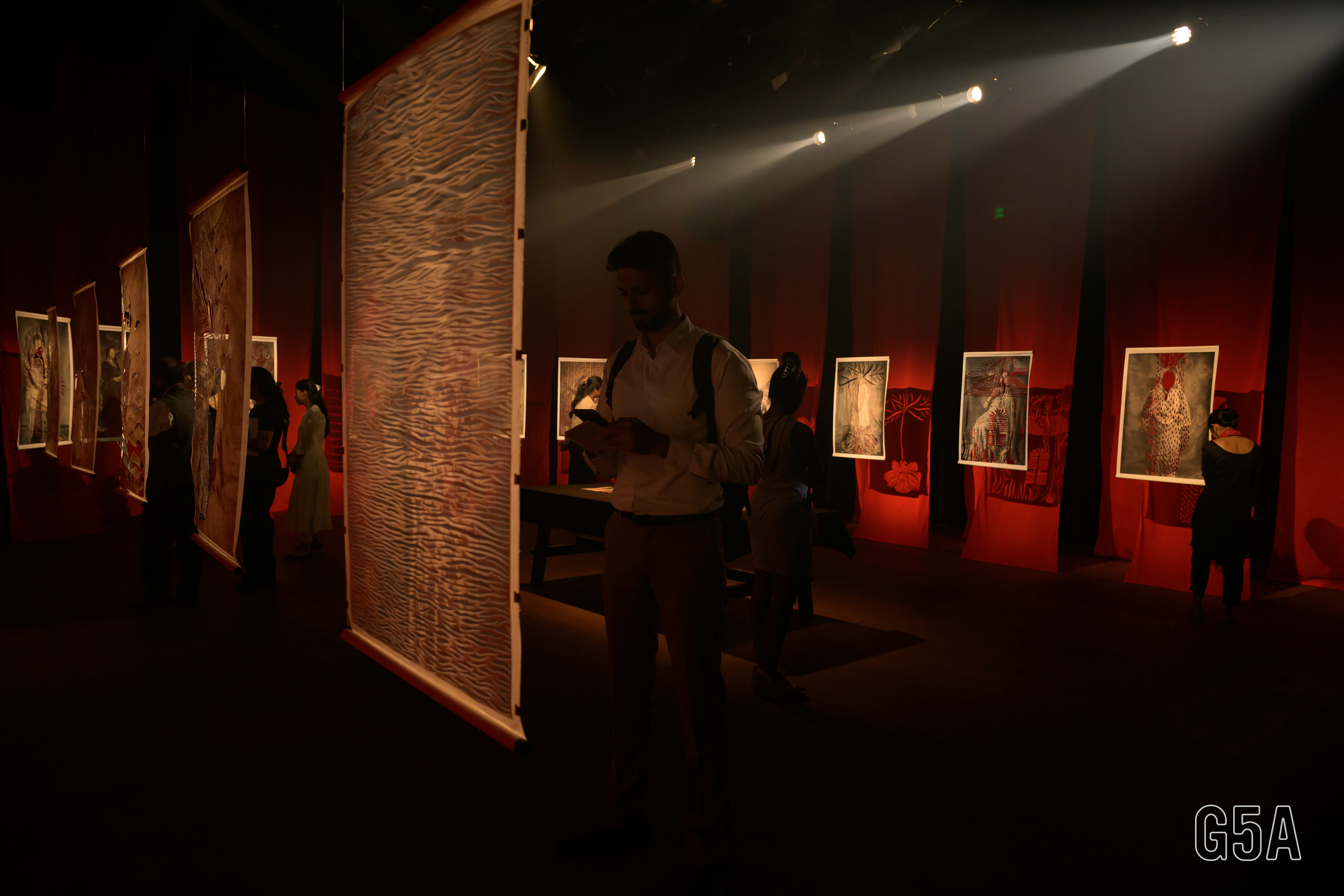

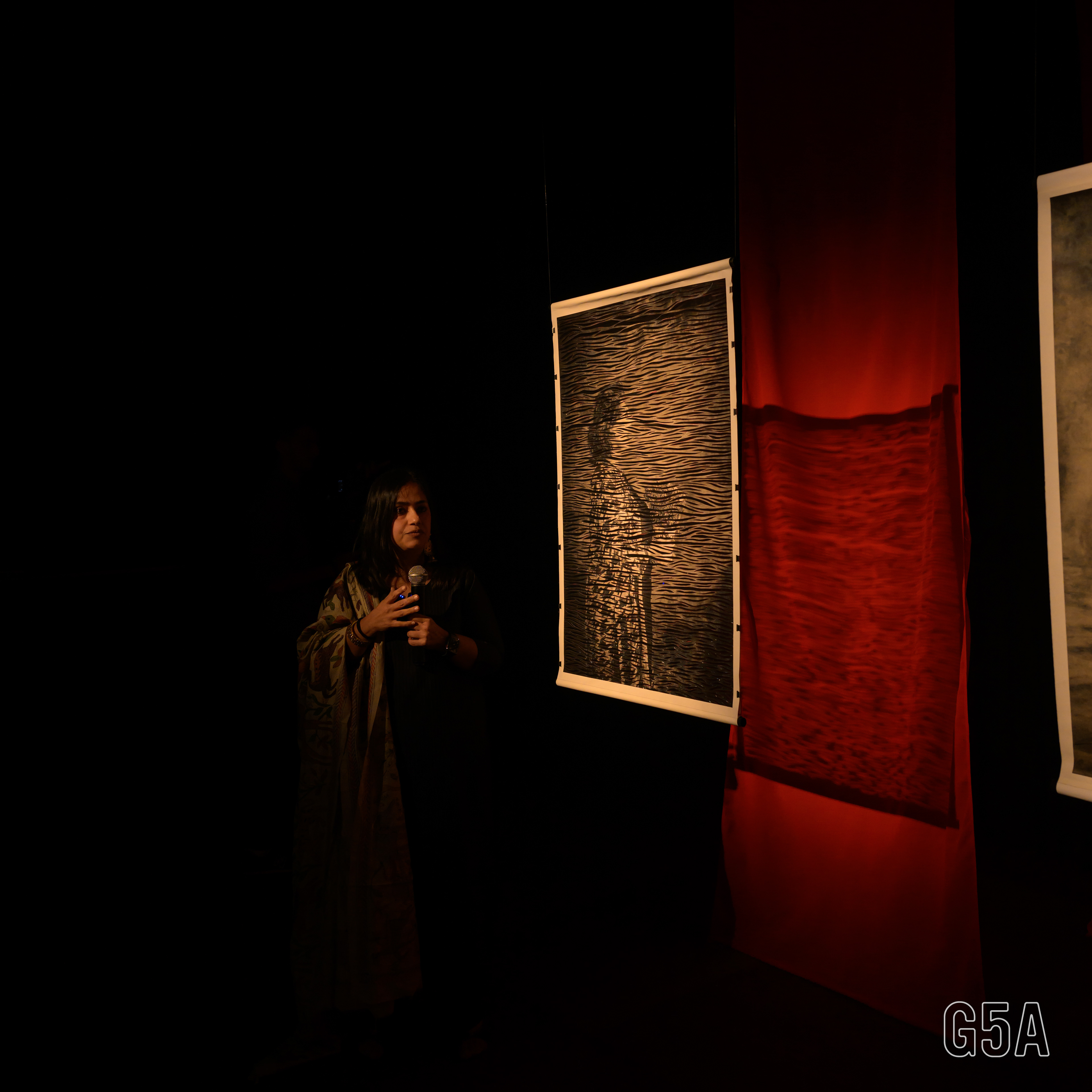

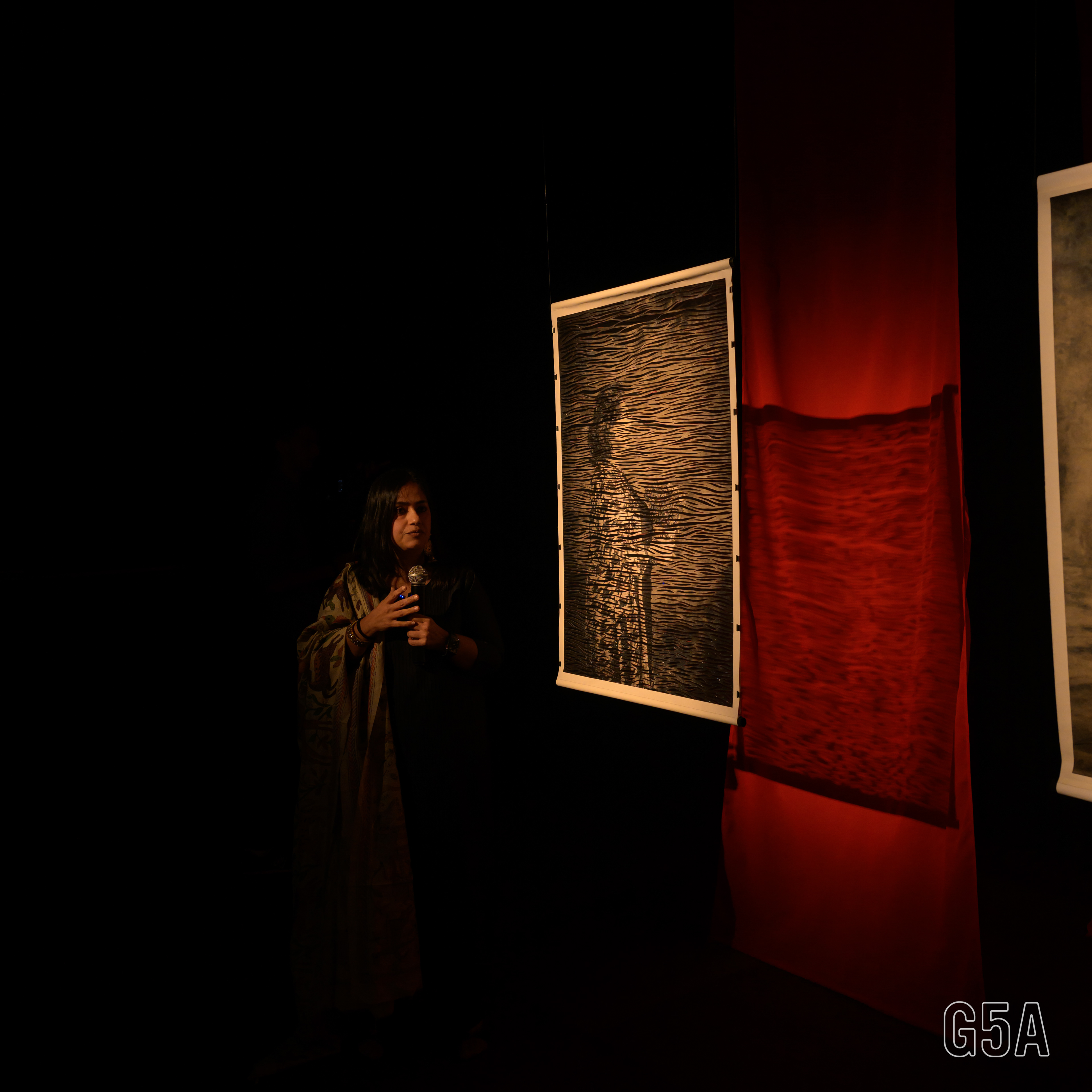

G5A Foundation Mumbai Solo Exhibition

G5A Foundation Mumbai Solo Exhibition

G5A Foundation Mumbai Solo Exhibition

G5A Foundation Mumbai Solo Exhibition

G5A Foundation Mumbai Solo Exhibition

G5A Foundation Mumbai Solo Exhibition

Madras Art Weekend, Chennai, India, Solo Exhibition

Madras Art Weekend, Chennai, India, Solo Exhibition

Madras Art Weekend, Chennai, India, Solo Exhibition

Madras Art Weekend, Chennai, India, Solo Exhibition

Madras Art Weekend, Chennai, India, Solo Exhibition

Madras Art Weekend, Chennai, India, Solo Exhibition

Madras Art Weekend, Chennai, India, Solo Exhibition

Madras Art Weekend, Chennai, India, Solo Exhibition

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK

FORMAT Festival, Derby, UK